Biotope Quarterly No.4

The Significance of Deciduous Trees in the Biotope

Advantest's biotope is based on the concept of restoring the original landscape of the Kanto Plain. Recent academic surveys have revealed that deciduous forests have existed on the Kanto Plain since ancient times.

In general, evergreen trees are more robust, so that deciduous forests will gradually lose out to evergreen forests if nothing interferes. Indeed, many parts of the virgin forest of the area consist of evergreens. On the other hand, in the cultivated woodland of the Kanto Plain, people long husbanded the deciduous forests to obtain firewood and tree nuts, resulting in stable coexistence. However, in recent years, due to the dominance of timber imports over domestic lumber, and the introduction of chemical fertilizers, the forest is no longer used by locals, and its area has shrunk.

Globally, conservationists applaud the cultivated woodland model of responsible forest stewardry. The word ‘Satoyama’ has even entered English, for instance in the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative, established at COP 10 (the 10th Ordinary Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity) in 2010.

Also, the deciduous trees that make up cultivated woodland allow lots of sunshine to fall into the forest in winter. The sun promotes the decomposition of fallen leaves, nurtures rich soil, and allows various flora and fauna to come together in search of sunlight and nourishment. From the viewpoint of biodiversity conservation, deciduous trees have great significance.

For the above reasons, maintenance and management of deciduous forests in parts of the biotope is a key focus of Advantest's conservation activities.

Caring for Deciduous Trees

As the number of saplings of oak trees, quercus serrata, etc. in the biotope grew, and began to block growth of mature trees, we started selective thinning in 2015. In thinned areas, sunlight promotes the growth of deciduous trees. If thinning is done all at once, it would burden the environment, so we will do it little by little, thinning each area at intervals of about 5 years.

Thinned logs are distributed to employees who want them for firewood. In the future, we are planning to cultivate mushrooms using logs, a traditional practice which embodies man's coexistence with deciduous trees.

Thinning trees. We will cut down trees at regular intervals using a chainsaw or a bulldozer.

Left) Deciduous trees after thinning. Logged trunks and branches are placed on the ground. Right) Logs arranged by size

Left) This kunugi was coppiced one year previously. A number of new branches are growing from the trunk.

Right) All but one of the branches were removed, allowing the strongest one to flourish.

Deciduous Trees of the Biotope

Kunugi

(Quercus acutissima)

Konara

(Quercus serrata)

The kunugi comes from southern Honshu, and the Konara is a broad-leaved tree that is common in many woods in Japan. The two varieties have many common features. Growth is fast and sap is abundant, attracting many beetles and other insects. The leaves remain on the branches for a while after changing color, and the logs are optimal for shiitake cultivation.

-

Kunugi -

Konara

How to tell kunugi and konara apart

Their bark has different characteristics.

Kunugi (left) has relatively thick bark and deep wrinkles, while konara (right) looks a little white overall.

Leaves and nuts. Left: kunugi, right: konara.

Kaede

Maple (Acer)

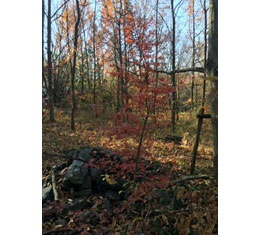

The biotope's maple trees were transplanted at the time of founding, in 2001, together with our oak and quercus. Maples do not grow as fast as kunugi or konara, but they have grown considerably over the course of the years. The brilliant red hue of maple leaves stands out in a mixed woodland area, even amidst the other autumn colors of the biotope.

-

Red maple leaves in autumn -

New maple saplings are growing in the biotope

Keyaki

(Zelkova serrata)

The tallest tree in our biotope. In 2015, when the winter arrived late, it kept its lush autumn foliage into November, but in 2016 the leaves turned colors in the same period as usual.

Enoki

(Celtis sinensis)

This stand of enoki graces the little island in the biotope's pond. In autumn its foliage turns bright yellow. The Great Purple Emperor butterfly, designated by the Japanese Entomological Society as the national butterfly of Japan, eats enoki leaves. However, Great Purple Emperors mainly inhabit mountainous areas, so they do not appear in our biotope.

Shirakashi

(Quercus myrsinifolia)

This is an evergreen tree that grows in our mixed forest along with deciduous trees. The leaves' lifespan is one year: when new leaves grow in spring, the old leaves fall all at once. It is said that if a forest is untended, it will transition to an all-evergreen forest consisting of a few unchanging species. For this reason, evergreen trees such as this shirakashi are preferentially harvested from the biotope. However, we are told that in the area surrounding the biotope, there used to be a lot of shirakashi, so we leave some in for balance.

Various Colors of Autumn

Why do leaves change color in the autumn, anyway? Their original green color is due to chlorophyll. Leaves also contain yellow carotenoids, but in lesser amounts than chlorophyll, so they look green, not yellow. However, when the temperature falls and leaves cannot work as effectively (since the light-independent reactions of photosynthesis depend on temperature-sensitive enzymes), their chlorophyll decomposes, and the remaining yellow carotenoids become conspicuous. The leaves of some trees also contain red pigments called anthocyanins. When cold temperatures and sunny weather intensify the concentrations of sugars in the leaves, anthocynanin production increases to allow the tree to pull in more nourishment from its leaves before they fall. This is which autumn colors are more vivid when it rains less, and the temperature differentials between day and night are high.

-

A maple tree turning colors in a gradated display -

Autumn konara

-

Yellow autumn foliage of a kunugi -

A hedge of autumn nishikigi

A Biotope First: Autumn Colors vs. Snow

On November 24, 2016, a strong cold front flowed into the Kanto region, and low pressure moved east on the southern coast of the Kanto region, so seasonal snow fell across a wide area. We observed snowfall of 6 cm in nearby Kumagaya in Saitama Prefecture and 4 cm in Maebashi in Gumma Prefecture, the first time in 66 years that this much snow has been seen in November.

Snow covering the autumn leaves was a sight unseen since the founding of the biotope. It was a very unusual and beautiful scene!