Disruption as a Natural Phenomenon

Forest fires, for example, seem to be destructive if considered in isolation. However, in reality, fires are beneficial for biodiversity: they allow sunshine to reach places where trees have grown too abundantly, attracting new flora and fauna to these zones of renewal. In this way, phenomena that greatly change the environment and trigger regeneration or the introduction of new species can be collectively called "disturbances," rather than destructive events. In addition to forest fires, floods and gales, earthquakes and tsunamis, lightning strikes, avalanches and landslides, and volcanic eruptions are all loci of disruption.

People tend to try to control disruption. But in recent years, "green infrastructure," applied to flood control, agricultural land improvement, urban development, etc., has sought to leverage natural resilience to cope with disturbances. One example is a comprehensive flood control method including masonry and landscaping that makes it easier for living creatures to regroup, as well as utilization of reservoir ponds, rather than uniformly plastering river banks with concrete, as was formerly common in Japan. It is now accepted that we should try to preserve biodiversity by working around disturbances caused by natural phenomena and fostering diverse natural environments.

Artificial Disturbances & the Biotope

On the other hand, there are also disturbances caused by human beings, such as deforestation, grass cutting and burning, and dredging of rivers and lakes. Excessive logging and the like can lead to environmental destruction and desertification, but moderate disturbances enhance the natural environment by encouraging regenerative cycles.

Advantest's biotope aims to restore "the lost landscape of the Kanto plain". This is not untouched nature, but satoyama, a landscape shaped by human stewardship of our natural inheritance. Therefore, we carry out mowing and thinning work. These moderate disturbances help to create places where diverse creatures can gather and thrive.

The lotuses of Kodai Hasu no Sato, a park located in Gyoda City, Saitama Prefecture, close to the biotope, are an example of the benefits of artificial disturbances: Seeds that had been buried in the ground for many years were uncovered when a pond was dug, and now bloom beautifully.

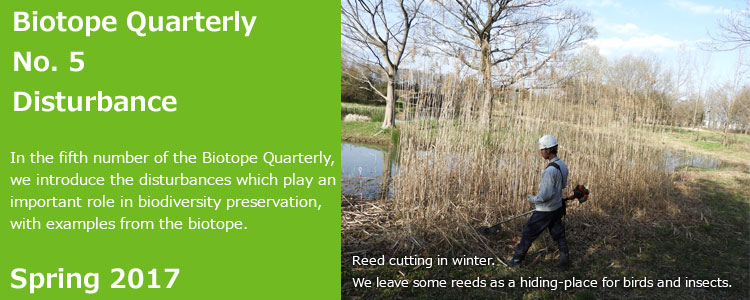

At the biotope pond, we regularly harvest bulrushes, reeds, etc. Reeds were traditionally harvested as a material for thatching and other purposes. Also, aquatic plants such as reeds have a water purification effect by absorbing dirt. If they are allowed to die in place, the dirt they absorbed will return to the pond.

The Close Relationship Between Disruption & the Flowers in the Biotope

- Mizokoju

-

Scientific name: Salvia plebeian

Flowers in May - June

Status: Near Threatened Species (Ministry of the Environment), Near Threatened Species (Gunma Prefecture)

Although mizokoji was originally not found in the biotope, it seems that it has drifted in from nearby. You can see it on the sunny banks of streams and in meadows as well as ditches. Since the cycle from germination to flowering and death lasts over 2 years, the appearance of this flower changes in a 2-year cycle.

In the biotope, we cut mizokoji with a lawnmower when the seeds are perfectly ripe and the stems are dead. Its scattered seeds are said to have a tendency to increase the number of plants the following year when they receive a stimulus, such as periodic grass cutting, rather than being neglected. This phenomenon has also been confirmed by research on plants of other species. In fruit trees, restricting growth can produce more delicious fruit, and roses are often tied down so that more flowers will bloom. It is said that this is due to ecological characteristics unique to plants: if threatened with death, they bloom or fruit so as to leave descendants.

- Ibokusa

-

Scientific name: Aneilema keisak

Flowers in August - October

In autumn 2015, we spotted ibokusa in the biotope for the first time in about ten years. Plowing a corner of a biotope to plant the near-threatened asaza, old seeds in the soil may have been turned over and then germinated. As the Japanese name of ibokusa implies, there is a legend that the juice of ibokusa can remove warts. An annual plant growing in wetlands, its pinkish-colored flowers last only about one day.

- Nejibana

-

Scientific name: Spiranthes sinesis var. Amoena

Flowers in April - September

We find these little orchids every year after mowing. They also grow in meadows outside the biotope. It seems that disturbances such as sunshine, which it only receives after mowing, and reduction of rival species, help nejibana grow. The flower is twisted like a screw, and it is very small, but if you look closely you can see the labellum which is characteristic of orchids.

- Navy Chrysanthemum

-

Scientific name: Aster ageratoides var. ovatus

Flowers in August - November

This flower also appeared in the 3rd issue of the Biotope Quarterly. We often see it in places where weeds were cut. Factors such as increased sunlight, and suppression of competitor species, seem to encourage its growth.

- Violet

-

Scientific name: Viola mandshurica

Violets are highly compatible with the satoyama landscape. However, in our biotope, even though we often spot the common Viola grypoceras variety, we have not seen true violets for the last 5 years. They may prefer an environment more heavily shaped by human hands, as we do see it in the neighborhood outside the biotope.

- Okawajisha (Water speedwell)

-

Scientific name: Veronica anagallis-aquatica

Disruption may also encourage the growth of certain alien species. In our biotope, okawajisha occasionally appears in asaza habitats. It crowds out and overwhelms not only asaza but also other plants if left alone, as it spreads large numbers of seeds. Incidentally, the native species of kawajisha has hybridized with okawajisha in the wild, and is now classified as a threatened species in the "Red Data" list maintained by the Ministry of the Environment.

Firewood Donations to Chino Biotope Forest

On March 3, 2017, we donated logs from oak trees and quercuses harvested in the biotope to the Chino Biotope Forest.

The Chino Biotope Forest is located within the municipal office precinct of Fujioka City, Gumma Prefecture, with an area of 10,000 m2. Hundreds of medaka, designated by the Ministry of the Environment as "Endangered Type II," thrive in the pond in the forest. As an opportunity to enhance their relationship with their local neighbors, they have been holding shiitake cultivation sessions using quercus logs. This time, more people participated and there were not enough logs, so Advantest donated logs from our biotope.

The Chino Biotope Forest and our biotope share the concept of preserving the traditional natural and rich satoyama of the Kanto plain, and regularly exchange ideas. We will further strengthen our cooperation to encourage more people to take an interest in biotopes and biodiversity.